I met the sweetest nurse this morning. Her name was Gabrielle. She’s from Co. Wexford and is looking forward to taking her children over to see her parents at half-term. I told her how much I love Ireland and stopped short of all the background stuff…but I did mention that the only other Gabrielle I know is my German penfriend – still call her my penfriend because we haven’t met for the last fifty six years. We write.

As you already know, sweet readers, I am a War Child born in May 1943 in Bedford, England. There is another War Child who has had a significant influence on my life, born in Celle, Germany, in July 1943, just eight weeks after me – Hedda Gabriele Weichler. The baby girl, I understood, was named after Ibsen’s heroine cos her Dad loved that play. Today she’s Hedda Luftmann, but always Hedda Gabriele in my mind.

My early years were spent in an anti-German world. Films, songs, snatches of conversation, men and women in military uniforms, tanks and jeeps on roads, Civil Defence, air-raid shelters, toy guns, children’s war games with toy soldiers… and in the skies…. well, Celle, like Bedford, was close to military airfields, so as we grew up, Hedda and I shared the sights and sounds of bomber and fighter planes flying low over the town to and from their bases.

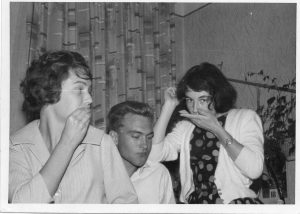

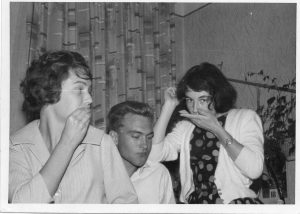

We wrote to each other from 1959. That was the year I started learning German and after four years of learning French, I fell in love with German’s depth of music and clarity of structure. When we were sixteen, an exchange visit between our schools was on offer. I didn’t dream my parents would be able to pay for it, let alone agree to it – but, for which they have my eternal gratitude, they found a way to do it and in April 1960, Hedda came to Bedford.

Of course, we did the whole sharing of what goes on in an English girls’ school and the group visits to London, to Cambridge and to Whipsnade Zoo. Yet what stayed with me was memories of Hedda in my home. I loved the way she called my parents Mum and Dad. I think now of how daunting it must have been for her to suddenly have three English brothers – and the youngest just six years old. Hedda is an only child and I’m one of four children. Our home was one where all the adults chipped in to find ways to make ends meet.

Meals were more fun than usual with Hedda, like Sunday dinner with Yorkshire pud and gravy first, then vegetables, followed by rice pudding. Heaven knows what she thought! One teatime I remember as clearly as a starry night! She took a slice of my Mum’s ginger cake and solemnly placed it between two dry (no margerine) slices of bread and sat happily munching it. I also remember her telling me that her Mum had asked her not to mix with any existentialists! She was certainly mixing with Geordies in our home – and to this day I wonder what she made of the accents outside compared to the inside accents of our daily life in exile from Tyneside. She loved to listen to my Nan.

In the summer of 1960, our school group saw Europe for the first time. From Calais onward, I looked out on miles of cornfields as we passed through Belgium and on up into Lower Saxony. The coach which met us delivered each girl to her penfriend’s house and I started to notice windows for the first time. The little houses had plants on every window sill. The net curtain didn’t cover the whole window like a shroud as it did at home, but hung high above the plants, giving them a frilly and sometimes a coloured frame. Windows are still very important to me. Like eyes.

Hedda lived in an apartment on the top floor of an older house – something totally new to me. It seemed dark at first, but I soon got used to the ways of things. I met Mutti. She has always been my Mutti. I know now how hard she must have worked to keep things going in that little home. Out early in the morning to a job in the court in town. Mutti was always smart, with short dark hair and a straight bearing. She loved, or needed, her cigarettes. At first, she made me anxious, with something of the stern primary school teacher about her, but I gradually learned about the love offered in their home.

And I met Omi, Mutti’s mum – and Hedda’s Nan. Omi lived with us – a small, active woman, with her grey hair drawn gently into a loose bun and always wearing her apron over her dark dress. I did not find it easy to understand Omi’s words, but I understood the woman and tried to respond to her. One day she showed me a small black and white photo, no bigger than two inches square, with a large family group on it. I remember holding it up between my fingers to look at it as she repeated ‘Meine Familie.’ Gradually I understood that this was all her family in East Germany and that she was cut off from them.

I met Hedda’s cousin Rainer, his mother Tante Anneliese and his father Onkel Fritz. Rainer was the closest Hedda had to a brother and he visited most days or we would catch him rolling along on the cycle path to school in the early morning. School in Germany started early.

Coffee and Torte in the late afternoon with Mutti and Tante Anneliese was a new treat for me. Coffee? I’d hardly smelt a cup of coffee until I was in Germany. I’d seen Camp Coffee liquid in a bottle at home, but this was the real thing. The food was exotic: raw fish, fresh salad, cold meats, asparagus, quark, sauerkraut and black bread – a whole new realm, far removed from the bread and dripping, bread and marmite, bread and rhubarb and ginger jam or home-made scones and ginger cake at home. Peanuts too – we seemed always to have peanuts to dip into.

Sudwall, where Hedda lived, is a road that runs next to the Franzosische Garten in Celle – a beauty spot. The old town of Celle escaped the bombing and looked to me like a fairy tale set, with painted house fronts in many colours and open spaces. Sometimes, on the way home in the evening, we’d come across British soldiers making their way back to the barracks and they always seemed scary and so out-of-place to me.

We went to Hanover and sat in the Herrenhausen Gardens, while fountains played alongside a son- et- lumiere performance of Handel’s Water Music. We went to Luneburg and to the Luneburger Heide, where I had my first glimpse of watchtowers and barbed wire, the symbols of a Cold War. Celle, it turns out, was one of the larger towns en route to what had been the Bergen-Belsen POW and concentration camp. I knew nothing of this. Things might have been said to me about it, but neither my German nor my inclination were strong enough to take it in. Later I learned that it was on Luneburger Heide on 4th May 1945 that the German army made its unconditional surrender. Hostilities were to cease from eight o’clock on May 5th, 1945. Hedda and I were the same age that my beautiful granddaughter Ella is now – almost two years old. And as I write, there is a ceasefire in Syria. May it hold.

I missed knowing Hedda’s Dad. I knew he had died – that was all. I didn’t ask any questions. He was very present in that home and I would love to have met him. It was many years later, when Mutti died that I heard from Hedda he had been a journalist before the war and that she now has all his letters. There’s a bit of a writer in Hedda Gabriele too. Over the years we’ve shared baby clothes, sent postcards, letters, music, Christmas gifts, photos – especially of our beloved grandchildren – and all this I see as a precious gift. Her father was killed at Stalingrad the year we were born, in 1943.

The gift they gave me is the insight into what people like Mutti, Omi and Hedda had lived through and how they loved and cared for me. I sensed the futility of war and these things live in my heart. Today, Hedda and Heinrich sing in Munster Capelle Choir and their music and singing sounds to me like managed hopes and their daughters, Iris and Julia, with husbands Stefan and Ole and the grandchildren Marthe, Justus and Malte, part of the beloved families we are blessed with.

aus Die Achte Elegie

Wir haben nie, nicht einen einzigen Tag,

den reinen Raum vor uns, in den die Blumen

unendlich aufgehn. Immer ist es Welt

und niemals Nirgends ohne Nicht: das Reine,

Unuberwachte, das man atmet und

unendlich weiss und nicht begehrt. Als Kind

verliert sich eins im Stilln an dies und wird

geruttelt. Oder jener stirbt und ists.

Rainer Maria Rilke

from The Eighth Elegy

We never, not for a single day, have

before us the pure space into which flowers

endlessly open. Always it is world,

and never nowhere without the no: that pure

unsurveilled element one breathes and

infinitely knows, without desiring. As a child,

one may lose oneself to it in silence, and be

shaken back. Or die and be it.