Dear Readers, let me tell you a bit about my Dad. He was one of six children brought up in Jarrow, Co. Durham in the 1920s.

What I remember most about him physically are the freckles on the top of his head – where there used to be black hair. He always said he had ‘lost his hair at sea.’ I like to think that if it had to be anywhere, the sea is the best place…I used to kiss those freckles as he sat on the step in the back garden, reflecting on life, as you do… the last freckle-kiss was in August 1962. I loved his voice – and often still hear it at different times – and whenever I hear a Geordie speak, I have to stop and listen to the detail to work out how far from Jarrow the voice comes. He wasn’t tall – about 5’8″ I should think and he had a sturdy body, with strong hands. I see them clearly on a steering wheel. But he was a big man.

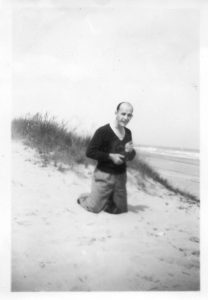

My earliest memory of him is of a photograph – a man called Cyril, a black and white photo of a man in naval uniform, with a cap on his head – smiling at me.

Whenever I had a sweet, I shared it with the photograph. and when I went to bed, the photo got a kiss. There is also the smell of tar and oil on ropes alongside ships in a dockyard which is always the smell of my Dad to me – and a gangplank is a very familiar object to me. I must have been very young when I first walked the plank to him.

I didn’t get to know my Dad until after I was two and he’d come home from the Merchant Navy, but we used to visit him in different ports when the tanker was in. I’m sure I must have been a much-welcomed small person on those visits – sailors are so quick to make you feel part of the ship’s family. My heart still stirs when I’m near ships and I’m sure, from my life with him, that he never really left the sea.

As many children must have done after the war, I was told I used to turn to the photo at the mention of ‘Daddy’ – even when he was in the room. When he came home, then my three brothers started to arrive into our world…and I learned to fit in as a girl.

He loved gardening. How different is working in a garden from working in the engine-room of a tanker? Like the coalminers he had grown up with, he treasured growing things from the darkness of the earth. He planned his garden carefully, built trellises from the branches of trees, built rockeries from the rubble left by builders on our council estate and planted hawthorns, lavender, privet, London Pride, cornflowers, Canterbury bells, lupins, stocks and snow-in-summer. He laid out his lawn. The rectangular middle bed set between two half-moon beds – cared for with great precision. His garden won a local prize – just reward for his quiet devotion and care.

The back garden was full of vegetables – potatoes, carrots, broad beans, runner beans, cabbage – and these made up the parish where Butch the tortoise lived.

My Grandad – ‘Pop’ – spent alot of time in the back garden tending the vegetables and our rabbit, ‘Thumper’, had a palace of a hutch at the back of the house and was never short of hugs or vegetables. I remember standing on the path in the early morning, with sleep in my eyes, watching Pop hoeing.

Some of the happiest times were the Sunday morning walks with my Dad. Wearing our best coats, hats, gloves and scarves we were off on an adventure together, feeling safe with him beside us. Off the estate and over the bridge to Harrowden – along the lane and through the gate to ‘the moors’, as we called the water meadows that draped the old roads and tracks between villages. One of my memories is of tall grasses, buttercups, tiny streams and jumping over cow pats. and Dad with his Kodak Brownie box camera, lining us up to smile at him – marvelling at his magic. Photographs were very precious in those days – and still are, to me.

Or we might turn left after the bridge and the little Methodist chapel, towards Cardington village, gazing at the dark shapes of hangars across the fields in the distance or gazing up at the ‘weather balloons’ tethered from the airfield and floating high above us. I remember tall elms as we passed the little cottages where the farmworkers lived – set amidst the corn, barley and brussels sprout fields.

In Cardington village we would walk past the old church and almshouses to the pub on the corner where the miniature railway ran round the garden. One short ride, with the tiny engine puffing away while my Dad had his pint, then another photograph and a happy, tired walk home. I think he must have loved those rural spots and must have loved to share them with us.

At home though, there was always an elephant in the room: my Dad’s heart.

When I was three going on four I remember him propped up by pillows in bed in the front room, occasionally passing the time with practising the needlepoint embroidery my Mum was teaching him. So we grew up understanding that if we weren’t quiet Daddy’s life would be in danger. No slamming doors, no shouting and no friends to play with us in the house.

I was told it was rheumatic fever wrongly diagnosed as flu that damaged the valve in his heart, but later in my life, Uncle Cyril – Dad’s sister Audrey’s husband, told me that towards the end of the war my Dad’s ship was bombed in the Channel and that he was one of the survivors picked up. This was never discussed at home it seems, but he was certainly a broken man in those early years of my life.

In September 1962, when my first child Maria was four weeks old, my Dad died. He adored my baby girl and brought a pink sleep suit for her on one of the few trips he made from Bedford to Peterborough to visit me. It gave him the chance to have her all to himself, cradled in his arms while I got on with a few jobs. I’ve often thought how hard it must have been to be at sea and have a baby girl you long to cradle so far away at home. Those last days of his life were when I really came to know how much he loved me.

On the morning of September 12th 1962 I pushed my baby Maria in her pram along Park Road and stopped at the phone box to ring Mum at work.

“No, she’s not in today. Didn’t you know? Your dad died last night”, the voice said.

I remember reeling against the phone box, my cheek on the cold glass and trying to catch my breath as I stared at my baby in the pram outside. It’s hard to describe how I felt after hearing those words in that fashion, but I managed to walk back to the little flat with the pram to support me.

Late that morning my parents’ next door neighbour drove in his car to bring Les, my nine year old brother to stay with me. We were both quietly looking after the baby together most of the day, but by the evening, around nine o’clock I felt so alone I ordered a taxi to drive us home to Bedford. I remember sitting in the back of the taxi with my brother asleep cradled in one arm and my baby asleep in the other arm. The taxi driver was quiet and kind. I looked from one sleeping child to the other through my tears and watched the fields as we drove through the night.

It was autumn, early autumn – just moving into that time of year when the stubble is burned after the harvest.”Swaling”, they call it. I love that word.

A dark countryside, a warm night, a gentle breeze and there were small, dark figures moving around crazy, dazzling, dancing tracts of field – shining out at the little cars passing and shining up at the little planes flying over them, where people would peer down and ask “What’s that?”.

It’s funny how unfamiliar swaling seems. Not like the tractor ploughing while Icarus falls from the sky and not like the haymaking in traditional rural scenes. Not like the poppies in the wheat or on all the greetings cards and not like the polythene-wrapped silage for winter grazing.

A clean, quiet, night-time activity this. A soulmate for me.

I think I used to go and search to find it again in later years over in East Anglia. It sterilises the earth – baptism by fire I call it.

The taxi driver carried Les into the house for me and laid him gently on the settee.

A Letter to my Father

Oldham, 19th April 2018

My darling Dad,

Twelve days ago you would have been ninety eight but you died at forty two so you’re forever young to me. I’m just writing a few lines to thank you for being around so close to us while Geoff had his heart operations last month.

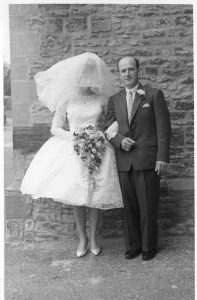

Do you remember the morning in April 1962 when we were the only two people in the house before we set off to the church in Elstow? You were standing at the top of the stairs with me at the bottom in my Dorothy Perkins wedding dress and you asked “Am I alright Pet?”. You looked so neat.

“Are you ready?” you asked with a smile. I wonder how you really felt? And off we went.

At the time, you were waiting to hear from St. Thomas’ Hospital in London to say they were ready to fix your heart. I’d spent my whole life with you worrying about the mysteries of your heart, your fatigue, your breathlessness and all the unspoken fears you never shared with me.

Well Dad, what a wonder and a privilege it was to watch our Geoff having his life saved in a London hospital – Royal Brompton. He had your courage. I just want you to know he has lived through all the unspoken fears and found the strength he needed to find his way through each long minute, each procedure and eventually, each small step back into life.

He’s home now and feeding the birds in his garden. The sun’s out today, so he’ll be trying a few more steps with Pat beside him. And Maria is growing Morning Glories from seed for my garden.

I love you to the moon and back.

Eileen x

April 21st 2018